While regulations on pesticides are the subject of intense debate at both national and European level, what do we really know about alternatives to these products for controlling weeds? Here is an overview of the various alternatives available.

It is impossible to mention their name without provoking strong reactions. Pesticides are the subject of heated debate, which can quickly become emotional, between farmers who claim they have no viable alternatives, products that often lose their effectiveness with repeated use, and people who are concerned about protecting their environment and their health.

In response to these concerns, in 2018 the French government strengthened its national action plan to reduce pesticide use by 2025, including a commitment to phase out the use of glyphosate. However, in 2024, the government suspended this plan in response to protests from the agricultural sector. A new national plan, Stratégie Ecophyto 2030, promotes a new approach by providing funding for research into alternatives to the most dangerous pesticides.

As a result, the commitments made in 2018 on reducing pesticides and phasing out glyphosate have been modified, and the initial targets are no longer relevant.

This product is used to combat one of farmers' worst enemies: weeds. But to get rid of these unwanted pests, the agricultural world as a whole is also working on alternatives that are more respectful of the environment and human health. This field has seen significant technological innovations in recent years. Let's take a look at the rationale behind weed control measures and these new initiatives.

What are “weeds” and “herbicides” in agriculture?

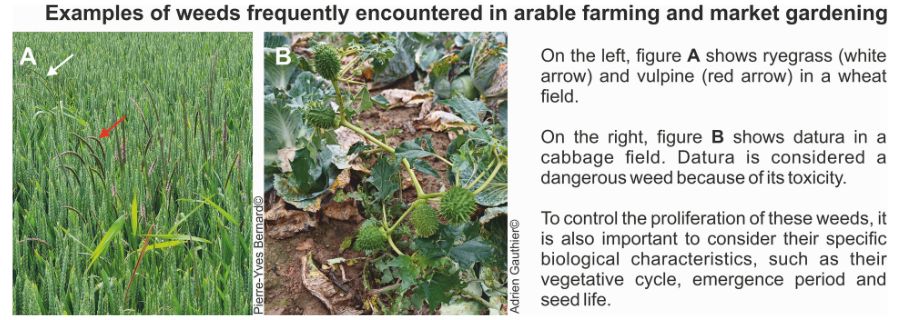

Let's start with an observation: weeds are probably misnamed. The term actually refers to plants that grow spontaneously in cultivated fields. They are not bad in themselves, but simply in the place where they are found. For example, datura (Datura stramonium) and poppy (Papaver rhoeas) are used as ornamental plants in our gardens, but are toxic and therefore undesirable in fields. Foxtail (Alopecurus myosuroides) and ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) are not toxic, but compete with cultivated plants.

Scientists prefer the term “adventitious,” which comes from the Latin adventicius, meaning “coming from outside.”

To combat these invasive plants, farmers often use herbicides, which are active substances designed to eliminate weeds. One of the best known to the general public is glyphosate. They are also referred to as “chemical weed killers” because most are synthetic molecules. A herbicide is designed to destroy weeds without affecting the development of the crop plant. To achieve this, it is used at a strategic time to destroy weeds without impacting the growth of the crop plants.

Herbicides generally target the physiological and metabolic processes of weeds, causing them to die or stop growing.

Why are weeds considered harmful?

But why try to get rid of weeds? Weeds pose a number of problems for farmers. They can directly reduce crop yields by competing for resources such as water and nutrients in the soil. In addition, by producing seeds, weeds can become more and more numerous each year until they reach a number per square meter that is difficult for farmers to control. The harm can also be indirect, for example by complicating harvesting conditions and reducing crop quality. An additional step is then required to remove weed seeds from the crop.

However, repeated use of herbicides can be counterproductive, leading to the selection and development of resistance to the active substances in the plants that are being targeted. This is similar to how overuse of antibiotics can lead to antibiotic resistance. For example, two weed species in winter cereal fields, ryegrass and field foxtail, are currently causing weed control problems for French farmers because they are invasive and difficult to control with current herbicides (Figure A).

But herbicides are also controversial for other reasons.

Why are herbicides controversial?

The use of these herbicides, and pesticides in general, can pose risks to human health, primarily for farmers, as prolonged exposure can lead to conditions recognized as occupational diseases (cancer, infertility, neurological disorders, etc.).

In addition, herbicides can also have a negative impact on the environment by contaminating aquatic environments and drinking water resources. This pollution generates increasingly high clean-up costs for water management stakeholders and consumers.

Herbicides can also impact various organisms other than the targeted weeds, such as soil invertebrates, thereby reducing biodiversity in cultivated areas.

The withdrawal of a number of herbicides from the market due to their negative effects on health and the environment has therefore prompted farmers, agricultural advisors, and researchers to improve herbicide use and find alternatives.

So what are these alternatives to herbicides?

At the farmer level, there are various agronomic levers that can limit the presence of weeds and thus potentially limit the use of chemical control. Each lever taken individually is less effective than chemical control, but the combination of all the levers together represents a relevant option for agroecological weed control.

The choice of crop rotation, i.e. the type of crops and their order of succession, is a key lever for weed control. Repeating the same crops too frequently in the rotation, for example by exclusively planting winter crops in the fall, will favor weeds that have similar development cycles to the crop. Over the years, the population of this type of weed therefore becomes increasingly significant. The management of the intercrop period, which is the period between two main crops, also offers opportunities for weed control. Maintaining a plant cover on the ground prevents the soil from being left bare, which is conducive to weed growth.

Another important lever is soil cultivation, which encompasses a set of techniques that have been used in agriculture for a long time. Plowing is a particularly effective technique that involves turning over the topsoil of a cultivated field to a certain depth. Before sowing the crop, this effectively buries weed seeds and prevents them from germinating. To be more effective, it is important to plow only every 3 or 4 years to prevent buried seeds from returning to the surface, as seeds can have a lifespan of several years.

Mechanical weeding reduces the amount of weeds in the field through physical action, using specific equipment. For example, the blades of a hoe penetrate the soil, cutting the weeds present in the inter-rows (the area of the field between the rows of crops). In some cases, such as beet, many farmers already use this technique in addition to chemical weed control. There are also many guidance systems available to position these machines as close as possible to the crop row without damaging it: manual guidance, precision GPS, camera or other sensor detection systems are the most commonly used.

What are the prospects for research and development?

Alongside research and development in agroecology, the emergence of “digital” agriculture over the past decade offers innovative solutions that are little known to the general public. This type of agriculture relies on the use of digital science and technology to acquire data (satellites, sensors, smartphones, etc.), transfer it, store it, and process it, particularly through artificial intelligence.

In this technological context, various sensors have been developed to detect weeds in the field, both between rows and within rows, thus enabling localized weeding. Imaging coupled with AI makes it possible to distinguish weeds from the main crop and eliminate them by localized spraying of herbicide or by mechanical tillage.

The use of plant-based bioherbicides is another environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic chemical pesticides. Currently, the only product that can be used in field crops is pelargonic acid, but other products are being tested.

In the future, it may be possible to develop microbial bioherbicides (bacteria, viruses, fungi) that specifically target weeds.

Scientific research has also shown that certain beetles, adult seed-eating ground beetles, are capable of feeding on weed seeds and reducing the number of seeds in a field, but their use in the field is not yet effective.

Robotics is also a rapidly developing field for crop production. For example, an autonomous weeding robot is already being used in France in beet cultivation on small areas. It can sow seeds and, more importantly, weed mechanically on up to 6.5 hectares per day. It is powered by a solar panel, making it completely energy self-sufficient.

All these technologies have real short-term prospects. They will enable farmers to reduce their use of chemical pesticides, lower their carbon footprint by reducing their consumption of herbicides, and protect groundwater from herbicide pollution. Better knowledge of weed species and their dynamics in the field will, in all cases, enable them to be better anticipated and managed.

Pierre-Yves BERNARD, Associate Professor in Agronomy - Director of the Agrobiosciences College - Associate UR AGHYLE, UniLaSalle; Adrien Gauthier, Associate Professor in Phytopathology - AGHYLE Research Unit - Head of the Farming for the Future Career Path, UniLaSalle and Guillemette Garry, Associate Professor in Biology with a specialization in phytopathology, affiliated with the Aghyle Research Unit, UniLaSalle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.