Although Tolkien's universe is fascinating, it's not without its contradictions, particularly when it comes to geology. Far from realism, mountains, rivers and landscapes are places associated with a mythological universe.

J.R.R. Tolkien's universe occupies an emblematic place in fantasy literature. Works such as The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion bear witness to Tolkien's ability to create a world of great richness, populated by ancient civilizations, legendary creatures and spectacular landscapes.

Middle Earth, with its vast expanses, towering mountains and mysterious forests, is the setting for an epic that continues to captivate generations of readers. Peter Jackson's film adaptations have reinforced this phantasmagoria, and Prime Video's Rings of Power series continues in this direction, exploring new aspects of this universe while maintaining the visual appeal and mythological depth of the original work.

However, although Tolkien's universe is fascinating, it's not without its contradictions, particularly when it comes to geology. From mountains created by fantastic acts to volcanoes defying the laws of plate tectonics, the map of Middle-earth contains elements that escape conventional scientific explanation. This article examines these inconsistencies in the light of modern knowledge, putting Tolkien's geographical descriptions into perspective with their interpretation in Peter Jackson's films and the Prime Video series, while seeking to understand how the necessities of storytelling have sometimes prevailed over geological plausibility.

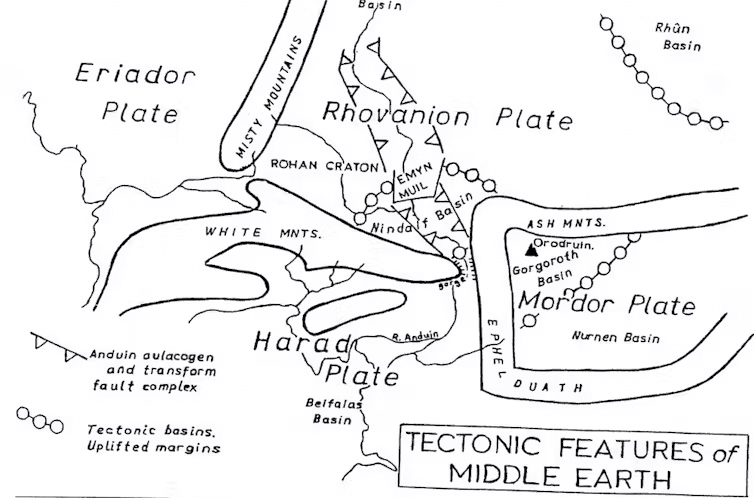

Tectonic reconstruction of Middle-earth by Reynolds (1974)

Geology and fantasy: an inevitable contradiction?

When Tolkien conceived Middle-earth, he wasn't looking to create a geologically accurate world, but to build a mythical, epic universe for his stories. Drawing on ancient myths and legends, particularly Norse mythology, he fashioned a world governed by supernatural forces rather than natural laws. Tolkien himself recognized the geological limitations of his world, admitting in correspondence that the geology of Middle-earth was “seriously flawed by the standards of modern science”. This shows that scientific precision was not his priority; he preferred the mythical aspect of his universe.

This choice is partly explained by the scientific context of the time. At the time Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings (in the 1930s and 1940s), the theory of plate tectonics was not yet well established, and it wasn't until the late 1960s that it became widely accepted. Knowledge of the formation of mountains and volcanoes was limited, and Tolkien, with no background in geology, imagined a world where landforms were shaped by supernatural forces. But even if he had written later, at a time when plate tectonics would have been well known, what would have prevented him from imagining it all, in a fantasy world? Was he expected to be scientifically irreproachable?

In this universe, mountains, rivers and forests are not mere features of the landscape, but the fruit of fantastic deeds or the site of mythological battles. For example, the Misty Mountains, created by Morgoth, are not the result of plate tectonics, but of a precise narrative intention. Similarly, the destruction of Númenor and the submergence of the ancient Land of Aman are more the result of mythological narratives, notably inspired by the myth of Atlantis, than of natural geological processes.

Geological inconsistencies in Tolkien's work

Tolkien's universe features marked geological inconsistencies, exacerbated by the author's narrative choices. Three notable examples are the Misty Mountains, Mordor and Mount Doom, and the White Mountains.

Misty Mountains: This range stretches for thousands of kilometers, with an almost perfect north-south orientation. In reality, such a formation would presuppose a major geological fault or a long tectonic history, absent from the story. Such a vast and linear mountain range would normally result from complex processes such as the collision of tectonic plates, with evidence of folding, faulting and major deformation, all of which are never mentioned in Tolkien's work. The absence of these geological details suggests that these mountains were created to serve narrative needs, rather than to reflect geological realities.

Mordor and Mount Doom

Mount Doom, a volcano that has been active for millennia, is the only one in Mordor, which is geologically unlikely without other volcanic manifestations. The induced eruption of Mount Doom, a central moment in the Rings of Power series, is an example of how narrative can override geological logic. In the series, this cataclysmic event is triggered intentionally, illustrating how mythic and narrative forces shape events to create Mordor, while departing from realistic geological processes.

Mount Doom (i.e., Mount Ngauruhoe)

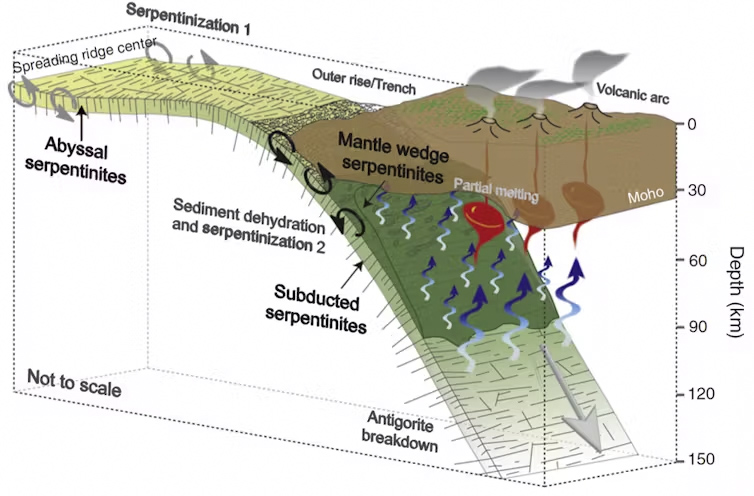

From a geological point of view, this type of volcano forms along convergence zones where an oceanic tectonic plate slides beneath a continental plate or another oceanic plate, a process known as subduction. As the plate plunges into the mantle, it undergoes an increase in temperature and pressure, causing the release of volatile fluids such as water. As these fluids escape the subducted plate, they lower the melting point of the overlying mantle, creating magma. This magma, less dense than the surrounding rock, rises to the surface to form volcanoes. These volcanoes are often located in mountain ranges like the Andes, or island arcs like the Lesser Antilles.

Example of a diagram illustrating the hydration of a subducting oceanic lithosphere at the origin of volcanism (after Deschamps et al., 2013)

White Mountains

Located well to the south, these mountains are described as permanently snow-covered, which is inconsistent with the region's climate.

In reality, mountains with permanent snow cover are generally located at high latitudes, close to the poles, or at very high altitudes where temperatures remain low all year round.

Misty Mountains, Unsplash.

However, the White Mountains lie well south of Middle-earth, in an area that would correspond roughly to a temperate or even subtropical climate in our world. In such a region, it is unlikely that a mountain range could remain permanently snow-covered, unless it reached extremely high altitudes, which is not the case for the White Mountains as described by Tolkien. The contrast between their geographical location and their perpetual snow cover is thus a climatic inconsistency, since a warmer, more temperate climate would make it difficult for snow to persist at moderate altitudes.

Why adaptations amplify geological inconsistencies

Peter Jackson's films and the Rings of Power series have accentuated these inconsistencies for visual and narrative reasons. The grandiose landscapes and extreme environments, while impressive, can sometimes defy geological verisimilitude. For example, Mordor is depicted as an arid land dominated by an isolated Mount Doom, creating a monumentality at the expense of scientific credibility. The induced eruption of Mount Doom in the Rings of Power series, a founding moment of the story, accentuates this aspect by introducing a spectacular, but geologically implausible element. Similarly, the White Mountains, with their snow-capped peaks, are even more majestic on screen, accentuating the epic aspect, but distorting the climatic reality.

Tolkien's universe, magnified by film and TV adaptations, goes beyond geological realities to serve an epic narrative and a mythology coherent in itself. If the geological inconsistencies are undeniable, they are more than compensated for by the narrative richness and immersion that this universe provides. Peter Jackson's films and the Rings of Power series, while amplifying certain inconsistencies, succeed in capturing the epic essence of Middle-earth, offering a captivating fictional world despite its scientific “flaws”.

About the authors

Olivier Pourret, Associate professor in Geochemistry and Scientific Integrity and Open Science Manager, UniLaSalle

Élodie Pourret-Saillet, Associate professor in structural geology, UniLaSalle