Rebound effects and “backfires” in certain cooperating farms

Through our study, we wanted to understand whether the exchange of effluents or feed between farms could give rise to a rebound effect and thus limit the environmental benefits of such cooperation.

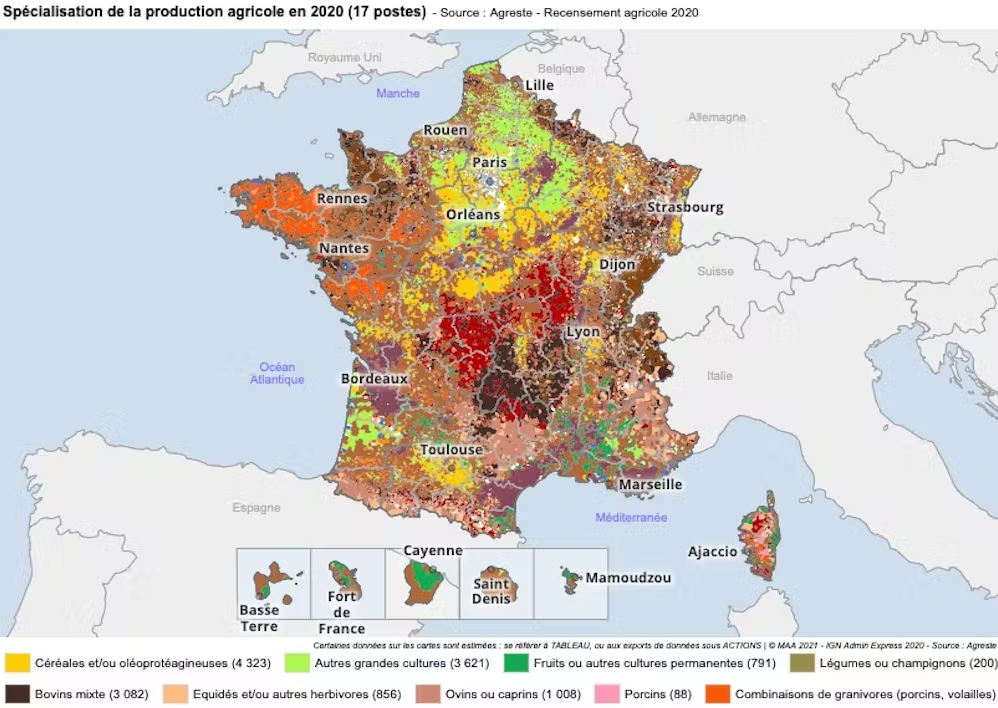

To do this, we conducted a survey of 18 farms in the Zaragoza region of Spain: half of the farms specialize in arable farming and the other half in livestock farming. Among these 18 farms, some exchange effluents or feed while others do not. We then calculated two indicators of the nitrogen rebound effect: one for arable farms to find out whether exchanges lead to lower consumption of synthetic fertilizers, and the other for livestock farms to find out whether exchanges limit the risk of nitrogen leaching into the environment.

Analysis of the results shows that only one in four arable farms uses less synthetic fertilizer thanks to effluent exchange. The other three experience not a rebound effect, but a “backfire” effect. They do use effluent, but also continue to apply synthetic fertilizers. Perhaps farmers fear that effluent alone will not provide enough nitrogen for their crops? They would then continue to use synthetic fertilizers to ensure good yields.

Among the livestock farms studied, two of the five farms that exchange manure have lower nitrogen losses than those that do not. The other three farms experience a rebound effect (one of them) or even a “backfire” effect (two of them). How can this be explained?

By exporting manure to other farms, these farms have freed themselves from a regulatory constraint that limits the number of animals per hectare in order to manage their manure properly. Without this constraint, they can raise more animals, thereby increasing their feed purchases, which increases the risk of nitrogen losses.

Through our study, we show that it is important to question the potential rebound effects in agriculture, as this is a subject that is too often overlooked when promoting new practices that are a priori beneficial to the environment. Indeed, in our study, rebound effects sometimes appeared when arable farming and livestock farming were reconnected through exchanges between farms.

In other words, cooperation between specialized farms does not necessarily lead to nitrogen savings and therefore environmental benefits. Nevertheless, this cooperation remains a promising avenue for reducing the negative impacts of agriculture while reaping the benefits of agricultural specialization, provided that rebound effects are avoided.

To this end, more ambitious measures on herd size or nitrogen management should be put in place to avoid intensifying agricultural production. Denmark has recently taken this direction by offering farmers the equivalent of $100 per ton to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilization.

Julia Jouan, Lecturer and researcher in agricultural economics, UniLaSalle; Matthieu Carof, Lecturer and researcher in agronomy, Institut Agro Rennes-Angers; Olivier Godinot, Senior lecturer in agronomy, and Thomas Nesme, Professor of agronomy at Bordeaux Sciences Agro, Inrae

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.