Agriculture is set to play a key role in the European Union's Green Pact, whose ambition is to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. This issue is all the more crucial as the Salon de l'agriculture returns from February 22 to March 2, 2024.

It has to be said that agricultural soils are ambivalent: they can be both a source of greenhouse gases or, on the contrary, sinks that trap them in the soil rather than in the atmosphere, preventing them from contributing to climate change.

So, best allies or underground threat? To understand this, we need to look at soil structure and, more specifically, the aggregates that reflect the organization of soil particles.

The microbial people who inhabit soils

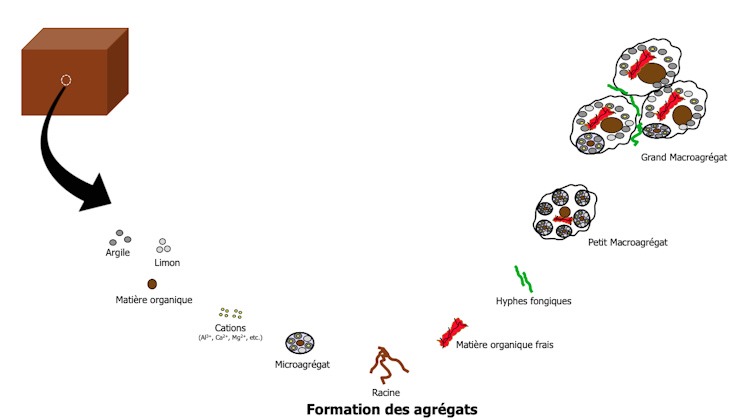

What lies beneath our feet is not a compact block, a solid, homogeneous substrate. Soil is made up of particles of varying sizes that come together, leaving spaces between them that fill with air or water. These pieces of various sizes are called aggregates. They are heterogeneous sets of particles that adhere firmly to one another, as shown in the figure below.

These aggregates constitute environments populated by micro-organisms. Among them are microbes which, as a result of their activity, produce greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O).

To understand where the molecules that will be transformed by microbes to produce greenhouse gases come from, we must first recall that plants capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air in order to manufacture matter (leaves, stems, wood...). Some of this material ends up in the soil in the form of leaf residues, stems or dead roots.

Depending on the situation, these residues can

- either be stabilized in aggregates, where they are inaccessible to micro-organisms due to the physical barrier formed by the aggregates themselves around the organic matter,

- or serve as food for micro-organisms, then be released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas.

Soils can therefore act as carbon sinks. By sequestering carbon from organic matter in the soil, they help reduce the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere.

It is the balance between the greenhouse gases emitted by soils and those trapped by them that will enable us to assess the beneficial or deleterious aspect of a soil - and, by the same token, of farming practices - on climate change.

A study to understand where greenhouse gases are formed in soils

We conducted a study to understand where these greenhouse gases are formed in the soil. Specifically, we examined how tillage and plant cover affect soil aggregates.

To do this, the study drew on previous work, in particular a field experiment conducted over almost 30 years in southern Brazil. This compared ploughed and unploughed plots, and plots with legume cover during intercropping periods with those without.

Samples of these soils were taken and the soil aggregates separated into three classes according to their size:

- large macroaggregates (between 2 and 9.5 mm),

- small macroaggregates (between 2 and 0.25 mm) and

- microaggregates (less than 0.25 mm).

In the laboratory, we then assessed methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from each soil aggregate class over a six-month period, as well as soil organic carbon (SOC) accumulation, in order to evaluate whether or not this offset emissions.

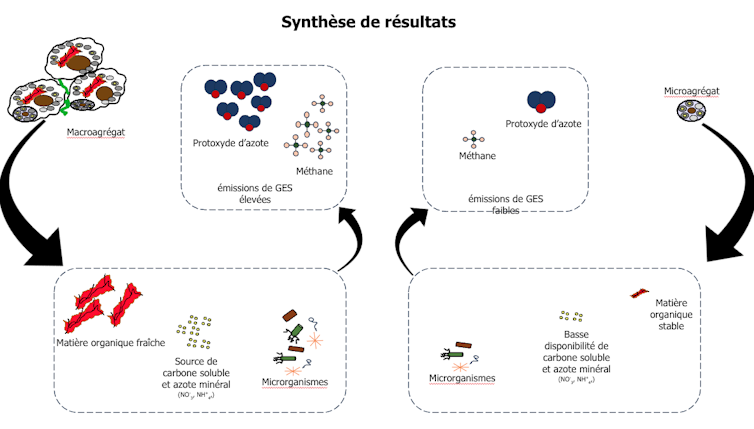

Our results show that microbial activity was most intense in large macroaggregates, particularly those found in no-till plots associated with legume cover crops. It was in these macroaggregates that emissions of greenhouse gases, particularly nitrous oxide - a powerful greenhouse gas - were highest.

The level of these emissions was correlated with the concentrations of nitrate and dissolved organic carbon in the macroaggregates, suggesting that the process responsible for nitrous oxide emissions is denitrification. This process is the conversion of nitrate to nitrous oxide by heterotrophic soil bacteria, which require a source of soluble carbon to achieve this conversion.

However, nitrous oxide emissions from these macroaggregates are totally offset by the accumulation of organic carbon on the one hand, and by the fixation of methane produced by the bacteria on the other. Methane is thus fixed in the soil thanks to an oxidation phenomenon known as methanotrophy: bacteria consume CH4 instead of producing it.

As a result, on a global scale, the macroaggregates in these samples trap more greenhouse gases than they release.

The benefits of no-till

At the level of individual plots, samples of no-till plots showed the most interesting greenhouse gas emission/absorption balance. For every kilogram of organic matter accumulated in the soil using no-till techniques, 69.4 mg CO2eq were captured, compared with 57.1 mg for ploughed plots.

The difference between the two lies in the macroaggregates, which are not broken down into smaller aggregates without ploughing. There are therefore more spaces (porosity) between the larger aggregates, allowing better oxygenation of the interstices and therefore easier oxidation of methane (CH4) and less denitrification. The presence of oxygen in the soil is the main enemy of methane- and nitrous oxide-producing bacteria: these are anaerobic bacteria that need an oxygen-free environment. As a result, less methane and nitrous oxide are emitted from these soils.

When microaggregates dominate, on the other hand, the carbon balance is less attractive: while nitrous oxide emissions are lower, methane consumption is limited, and organic carbon accumulation is lower. As a result, fewer greenhouse gases are trapped or eliminated, and the balance is more unfavorable.

The beneficial effect of no-till is further accentuated by the presence of leguminous cover crops in intercropping, which increase the amount of organic matter in the soil and thus the quantity of carbon stored.

Each kilogram of organic matter accumulated under leguminous cover corresponds to the storage of 74.7 mg CO2eq, compared with 51.8 mg CO2eq for soils with non-leguminous cover.

These results show that increasing the amount of organic matter in the soil through no-till systems and legume cover helps offset soil greenhouse gas emissions. This suggests that soil macroaggregates can act as an atmospheric carbon sink.

Flood risk in question

So, are no-till and direct seeding miracle solutions? No, because when samples are saturated with water, in order to reproduce the conditions of plots flooded by new climatic risks, water saturation of the soil prevents proper aeration. The absence of oxygen prevents methane oxidation and promotes denitrification, which emits nitrous oxide. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions are much higher in macroaggregates.

In all other cases, farming practices that use no-till and leguminous intercropping contribute to making our soils carbon sinks, thanks to the accumulation of this element in macroaggregates, which in turn helps combat climate change.

Murilo Veloso, Associate Professor in Soil Science, AGHYLE Unit, Rouen Campus, UniLaSalle; Anouk Lyver, PhD student in Soil Biology, UniLaSalle and Coline Deveautour, Associate Professor in Soil Microbial Ecology, UniLaSalle

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.